How I Built A Python Web Framework And Became An Open Source Maintainer

Inspirational thoughts and tips on starting and managing an open source project, based on my experience building Bocadillo, an asynchronous Python web framework.

It's been a while since I've written a blog post. Nearly two months, actually. So, where have I been?

On one side, the final year of my engineering studies has been taking up more of my time than I thought it would.

The other side of the story is — I've been working on building Bocadillo, an open source asynchronous Python web framework. The adventure, which started as a way for me to learn about Python async and the internals of a web framework, has been thrilling so far.

I had to put blogging aside for a bit, but I finally have the time to reflect on what's been going on!

In this blog post, I want to put on paper my thoughts about the whole process of building a web framework and especially on launching an open source project. I've already learnt a lot in the process, from programming techniques to project management and development tooling, so I wanted to share my experience with you!

Alright, so what's on the menu?

- We'll quickly cover what Bocadillo is.

- Then, we'll go through the story of how it became my first open source project.

- We'll wrap up with a series of tips I gathered from experience for those who want to start their own open source project!

First things first — let me introduce you to Bocadillo!

(This will be short and sweet, I promise.)

Introducing Bocadillo

Elevator pitch

Bocadillo is a modern Python web framework that provides a sane toolkit for building performant web applications and services using asynchronous programming. It is compatible with Python 3.6+ and MIT-licensed.

Key figures

Bocadillo's initial commit was on November 3rd, 2018. As of December 21st, i.e. a month and a half later, here's where Bocadillo stands:

- 500+ commits and 31 stars on the bocadilloproject/bocadillo repo — feel free to add yours!

- 10 releases to PyPI — latest being v0.7

- 8k+ downloads as measured by PePy

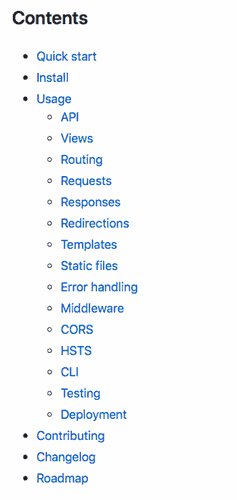

- About 30 pages of docs!

- 2 open source contributors — and many others welcome! 🥳

These figures are modest, but I'm already very happy with them.

If you want to support Bocadillo, you can:

Philosophy

In terms of philosophy, Bocadillo is beginner-friendly, but it aims at giving power-users the flexibility they need. It focuses on developer experience while encouraging best practices.

Besides, Bocadillo is not meant to be minimalist (but not a mastodon either). The idea is to include a carefully chosen set of included batteries, with sensible defaults, so that you can solve common problems and be productive right away.

Goals

My goal is that people embrace the new possibilities of async Python and that Bocadillo becomes a tool that helps people solve real-world problems more easily and efficiently.

There's still a lot of work ahead to get there, but the marathon has started!

Speaking of async Python, let me address a question you may have already asked yourself…

What with async?

Generally, a web app instance spends a lot (if not most) of its request processing time waiting for I/O to complete — API calls, database queries, filesystem operations. etc. Most of these operations are blocking, which typically limits performance if multiple clients are requesting the server.

The idea with async frameworks like Bocadillo is to build apps that do not block on I/O operations. To achieve this, we leverage asynchronous programming and recent additions to the Python language such as asyncio and async/await — available from Python 3.4+ and 3.6+ respectively. This allows us to consider processing a request as a task which is "scheduled" to run in a near future, i.e. when the CPU is avaiable.

As a result, beyond making better use of the CPU, this architecture has a very interesting advantage — we can now handle multiple requests concurrently.

(Note: I didn't write in parallel, as async still uses a single thread. Concurrency is not parallelism.)

This property ultimately results in more stable throughput and performance as the number of concurrent clients increases. From my own (yet to be published) benchmarks, Bocadillo keeps a steady processing rate whether it talks to 10 or 10,000 clients. On the other hand, "sync" frameworks like Flask or Django show a significant drop in reqs/sec in high concurrency settings.

Eager for more on Python asynchronous programming? Here are a few talks I recommend, perhaps to be watched in this order:

- Asynchronous Python for the Complete Beginner, Miguel Grinberg, Pycon 2017.

- Async/await in Python 3.5 and why it is awesome, Yuri Selivanov, EuroPython 2016.

- Fear and Awaiting in Async: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the Coroutine Dream, David Beazley, PyOhio 2016.

Implementation

Bocadillo is built on Uvicorn, the lightning-fast ASGI web server, and Starlette, a handy ASGI toolkit. Both were created by Tom Christie, a core contributor to the Django REST Framework (among other things).

Note: ASGI is the asynchronous equivalent to WSGI, i.e. a specification for how web servers should communicate with asynchronous Python web applications.

Features

What Bocadillo already has: requests, responses, views (function-based and classed-based), routes and route parameters, media types, redirections, templates, static files, background tasks, CORS, HSTS, GZip, "recipes" (a.k.a. blueprints), middleware, hooks, and even a CLI. There are more in the release pipeline!

One thing that Bocadillo does not have (yet), though, is a database layer. Most web apps or APIs I've built needed to persist data in some way, so I believe this (or at least an official recommendation for how to integrate an async database layer such as Tortoise ORM) should land into the framework at some point.

Hello, world!

Let's finish with the traditional "Hello, World" script!

# api.py

from bocadillo import API

api = API()

@api.route("/")

async def hello(req, res):

res.text = "Hello, World!"

if __name__ == "__main__":

api.run()

The story behind it all

Alright, enough of pitching Bocadillo! Now that you know what it is, I want to share with you the story that led me to write this very blog post.

How and why did it begin? What were some of the most meaningful events? Let's figure this out.

A learn-by-doing project

Bocadillo started as a way for me to learn more about the internals of a web framework. I wanted to get behind the scenes after nearly 2 years of using various Python and JS web frameworks. I wanted to know how it actually all worked.

To be clear, Bocadillo didn't start with a very detailed plan. Heck, I didn't even think about whether there was a need for an(other) Python async web framework. I wanted to learn more than anything else.

Let's reinvent the wheel, and release it ASAP

So there I was, on the 3rd of November, implementing features so common it felt like reinventing the wheel. These were features like requests, responses, views, routes or the application server. "Hundreds of web frameworks out there already solved these problems before", I thought…

But I didn't really care. As @FunkyBob kindly twitted to me:

Reinventing the wheel is an awesome way to learn… and sometimes what you learn is just how much your existing frameworks are doing for you.

A solid argument in favour of reinventing the wheel which made me realize how much Django is an absolute massive beast.

Anyway, this initial endeavour led me to release v0.1 on PyPI on the 4th of November. Just two days after the initial commit, people could already pip install bocadillo and build a minimal async web app. (Who said Python packaging was a pain? 🐍)

First signs of potential

After v0.1 was released, I carried on with implementing more features such as new types of responses or error handling.

On November 6th, v0.2.1 was out. That's when I began to realize that Bocadillo was a good candidate for my first full-blown open source project. The idea seemed appealing to me, so I went for it!

At that point, I hadn't disclosed anything about Bocadillo yet, not even to friends, so I wanted to make a first announcement. I chose to do it on Twitter.

Because Bocadillo's initial code design and implementation took heavy inspiration from Responder, Kenneth Reitz's own async framework, I decided to give a shoutout.

Kenneth's answer and the forthcoming reactions after he retweeted the announcement made me think that Bocadillo actually had potential.

In just a day, the repo got 20 stars (a personal record already!) and, although it may look trivial, I thought it was really cool.

Psst: if you want to help get Bocadillo known, you can star it too and spread the news!

So, after v0.2 was released, I felt motivated to keep working on Bocadillo, and add more features.

Up until I realized something…

Where are the docs? Like, real docs?

It was clear for me: I wanted Bocadillo to be my first open source project. I wanted to take it seriously in order to learn as much as I can from the process.

So, right from the start, I wrote an informative README, curated a CHANGELOG (with the help of keep a changelog) and added CONTRIBUTING guidelines. As more and more releases went out between November 6th and November 18th, I updated the changelog and documented new features in the repo's README.

Quickly though, this became impractical. The README was growing in size and it became hard to navigate, even with a table of contents.

That's when I realized I needed proper documentation.

If you think about it, good documentation is a sine qua non condition to having people use what you've built. And that lengthy README was not good documentation considering the size that Bocadillo was heading at.

Then, it hit me — a lot of large-scale open source tools, libraries or frameworks I use and love have a documentation site.

This is what led me to release v0.5 on November 18th with a major addition: a brand new docs site, which I built with VuePress and hosted on GitHub Pages.

On the necessity of good documentation — Joe Mancuso, creator of the Masonite framework, once shared with me this great piece of advice:

If it's not documented, it doesn't exist.

That's why I'm taking documentation very seriously and strive to make it as good as I can — and so should you with every project you're working on.

Then, while building the docs site, I made what I now consider as a very important move for any open source project…

Letting Bocadillo stand on its own feet

Before releasing the docs, I moved Bocadillo from a personal repo to its own GitHub organization, namely BocadilloProject.

The main motivation at the time was that I could use the organization's GitHub Pages domain bocadilloproject.github.io for the documentation. It is definitely way cleaner and more accessible than florimondmanca.github.io/bocadillo. 🙃

However, this had the positive effect of giving Bocadillo an online space of its own. It was not tied to my personal GitHub account anymore — the organisation was the new home for Bocadillo's source code.

Later, as I realized that Bocadillo announcements was taking over my personal Twitter account, I created a dedicated Twitter account.

The point is: it's important that an open source project lives outside of its creators.

Now, back to the story — on November 18th, I had a docs site up and running that people could visit. What next?

Opening up the development process

Up to November 20th, the way I kept track of the backlog and progress was via a private Trello board.

This was very practical to me: I use Trello for a variety of things. But I realized that people visiting the repo had no visibility on what was coming next or possible ways they could contribute.

In fact, from a visitor's perspective, I think the repo looked like just any other personal project — no issues, no PRs, just a ton of commits from a single person — and not a community-driven effort, i.e. what I'd like Bocadillo to become.

So, per the advice of a close friend of mine and inspired by this article by Dhanraj Acharya, I decided to open up the development process.

I converted all my Trello cards to GitHub issues, and added meaningful labels (see Sane GitHub labels by Dave Lunny) and description to them. I think the repo now provides better visibility on the project and feels more encouraging for newcomers.

I've learnt from this that open source is not only about opening the source code. You've got to be open about the development process, too.

I now hoped that, with the repo filled with issues and public PRs, it would attract its first open source contributors.

Spoiler alert: it did!

Yay! First contributors!

About at the same time, as Bocadillo grew in size, I began to feel the need for external advice. I was afraid that I might be taking bad design decisions or that the code could have been better. In short, I needed contributors.

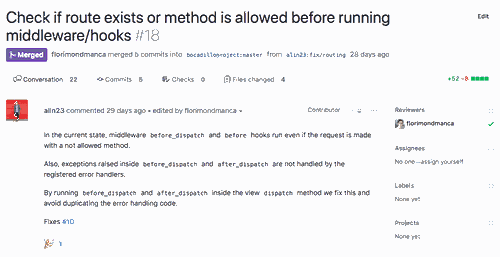

Luckily, still on November 20th, I had the great pleasure of welcoming the first contribution to the repo, in the form of Alin Panaitiu commenting on PR #3 for the new "hooks" feature.

Alin helped me fix a few things about the feature which I was initially unsure about myself, and suggested ways in which it could be made even more useful. He went as far as forking the repo and sending me a diff showing off a fix.

Later, on November 23rd, Alin got his first PR merged. Bocadillo had officially gained its first contributor! 🎉

As emotional as I can be, I was moved.

Even more so that Alin actually sticked around. In the v0.7 release, Alin contributed 2 new features (GZip and ASGI middleware), with a code-to-merged time of probably less than a few hours. Thanks Alin, great stuff!

Entering maintenance mode

From the end of November and onwards, the pace of the project slowed down a bit. On one hand, I was in a bit of a rush with school projects and exams being on the agenda, but that didn't explain everything. I was experiencing something else.

You see, in the beginning, committing code to Bocadillo felt very easy. There was barely any legacy so it was exciting and I had tons of ideas. Everything remained to be done.

But as more features were added in, it started feeling heavier. Releases took longer to get out — now taking a week instead of days. Testing, refactoring and documentation became major parts of the development process. Plus, I now managed Bocadillo's online presence too.

Don't get me wrong — I'm not complaining. In fact, I like that I got to go past the initial excitation and entered maintenance mode. Besides, it's definitely a normal shift for a project that's trying to gain momentum and reach out to the community.

I am now enjoying that working on Bocadillo doesn't have to take me nights like it used to in the beginning. Which leads me to the next point…

It's not a sprint, it's a marathon

I recently noticed that my attitude towards the project has changed.

Instead of rushing in to get features out as quickly as possible, and hoping that a burst of users would pop by, send stars en masse, love the framework and beg for more, I now felt more in peace with the idea that the project growth would be slow.

This stems from the fact that maintaining an open source project is a marathon, not a sprint.

Put differently, success should always be a by-product, not a goal.

You'll have noticed that Bocadillo's goal statement doesn't mention fame, nor a threshold number of users. It only states that I hope Bocadillo can help some people solve problems. If that is the case for at least one person, I'll consider it a win. If it becomes the case for a lot of people, I shall only consider it as a side effect.

This is it for the story behind building Bocadillo! As you may have noted from these discussions, I have been loving the experience so far, and I'm actually now convinced that I made the right decision when I decided to go past the fear of judgement and build my own web framework. Which leads me to the last section of this blog post.

Tips to start your own open source project

If there is one thing I want you to take away from reading this article, it's got to be this:

Open source is an awesome way to learn. You should start your own project today!

"Sounds great", you think, "but how should I proceed? Do you have any advice?"

Well, I do have some. 😋

First and foremost, learn as much as you can and make sure to enjoy yourself. Open source should never become a burden, and if it does, try to find ways in which you can start delegating or relying on the community to drive the project forward.

For the rest, brace yourselves — categorized bullet points ahead!

Note: if you're unsure about how to implement any of the following items and/or want to see how I used or configured the tools in practice, feel free to check out Bocadillo's repo and just copy the bits you're interested in — it's open source, after all!

Project definition

- Decide what you want to build.

- Decide why you want to build it — although it doesn't have to be deep or abstract, having a clear source of motivation helps.

- Think about scope and design philosophy: this will help make informed design decisions, and prevent feature creep.

- Decide who you are targetting: are your users web developers, sys admins, project managers…?

- Explicitly define user skills expectations: what should your users be familiar with, and how much?

- Decide how you will distribute your project (e.g. a PyPI package).

Marketing & Communication

- Build an identity: a name and a tagline at least. Make them short, catchy, and memorable. Showcase them everywhere (repo, PyPI page, docs site…).

- Create a visual identity: this is your logo and graphic charter. It's better to have an okay temporary logo than no logo at all.

- Decide on an entry point, i.e. a natural online location where people can look up your project. It can be the GitHub repo, a docs site, or whatever seems fit, but it should exist. (For Bocadillo, I believe this is the docs site.)

- Give your project a life of its own: it's a good idea to create a separate GitHub organisation or social media account.

- Use social media to communicate news, annoucements and tips, and start gathering people around the project (I use Twitter for this).

- Provide ways for people to see where you're heading at — a roadmap, a list of issues, an "unreleased" section in the CHANGELOG, etc.

Community

- Implement open source best practices: a proper README, contributing guidelines, a code of conduct, issue/PR templates, etc (use GitHub's checklist!). This will make the repo more welcoming to potential contributors, and show that you care about the community.

- Be supportive and kind to others. Thank them for their questions. Provide helpful resources.

- It might be a good idea to create a place for informal discussions. I recently decided to experiment with a Gitter chat room.

Project management

- Use GitHub issues to list your TODOs. That way, when wondering what you should work on next, just pick up a ticket and work on it!

- Set up meaningful issue labels (see Sane GitHub Labels).

- You can also set up a GitHub project to display your issues and PRs in a kanban board.

Code quality

- Set up a CI/CD pipeline.

- Be unforgiving on tests — besides ensuring your software works as it is intended to, they'll help you and everyone catch regressions and be confident when making changes (I use pytest as a testing framework).

- Measure test coverage (I use pytest-cov for pytest/coverage.py integration, and CodeCov for coverage reports).

- Enforce that PRs pass tests before merging.

- Every PR should contain all 3 items: code, tests and docs.

- Use a code formatter to reduce syntax/code style noise in code reviews (I use the opinionated Black formatter along with a pre-commit hook).

- If you don't have other reviewers, make PRs to yourself, let them settle and come back later. It's easier to see if the code is a mess after a few days.

Documentation

- Write a clear and informed README with at least a project description, install instructions, a quick start example and a link to the docs or somewhere users can learn more.

- Keep a changelog, you'll thank yourself later.

- Build a docs site if you're building more than a simple library (I use VuePress as a static site generator).

- Structure your docs: tutorials, discussions, how-to's, reference (tip: I use PydocMd to generate Markdown API reference straight from my Python docstrings).

- Remember: if it's not documented, it doesn't exist.

- Add pretty badges to your README (e.g. with shields.io).

Versioning and releasing

- Use semantic versioning (see SemVer).

- Automate version bumping with tools such as bumpversion.

- Automate the release pipeline. I use TravisCI to release tagged commits to PyPI.

- Set up special release branches. For example, I use

release/docsfor docs deployment andrelease/testfor releasing to Test PyPI.

Achievement unlocked?

This blog post is now coming to an end, so let's wrap up!

Although Bocadillo started as a way for me to learn more about the internals of a web framework, it has turned into a full-blown open source project.

With all the effort that already went into building the framework, documenting it, configuring the repo and managing releases, I now start to think of myself as an open source maintainer — which I think is a very enriching experience!

Even though I do take pride for what I have achieved so far, all of this is also very humbling. I now realize how challenging managing an open source project can be, let alone building a community around it. It's tough!

That said, I do believe that you should go for it and start your own open source project. It could be a simple tool or library, or an entire application framework — either way, you'll learn a lot in the process.

Of course, feel free to check out the Bocadillo repo if you seek ideas on structuring an open source project or setting up tooling. There are also tons of great resources on opensource.guide, so check this website out, too!

Thanks for reading through this article! As always, feedback is much appreciated. In particular, I'd love to hear your own stories on maintaining open source projects. Plus, if by any chance this article has inspired you, drop me a tweet!

Best wishes for this holiday season to you all. ✌️